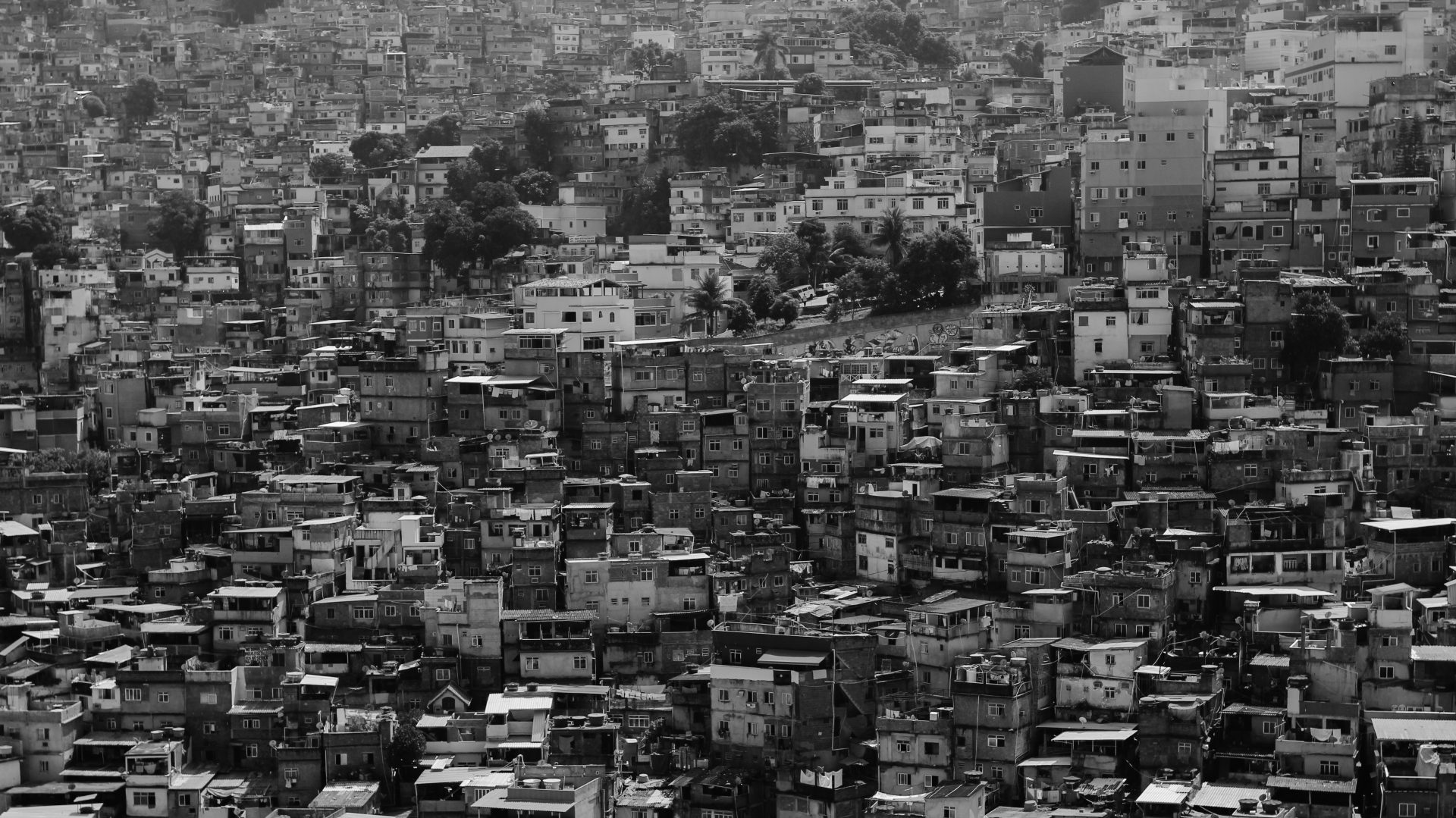

A recent study makes a case for the government to engage with slums, rather than relocating inhabitants to cities’ outskirts.

According to the UN, the share of urban Indians living in slums is 24 percent—about 100 million people. India’s government, in an attempt to rectify this situation, has made it a policy to give land to slum dwellers—though not in the more central areas of cities where the slums tend to be, but on the urban outskirts.

Published in: www.citylab.com // Mimi Kirk // June 9th, 2017

Saudamini Das, a researcher with the Institute of Economic Growth in New Delhi, says this strategy isn’t working. “Those who are relocated aren’t able to secure jobs outside the city,” she says. “They end up selling the land or giving it to relatives, and returning to more centrally located slums.”

Das’s recent research delves into what slum dwellers value when they choose housing, and has implications for this government policy. Through surveys of slum inhabitants in four Indian cities—Jaipur, Ludhiana, Mathura, and Ujjain—Das and two co-authors, Arup Mitra and Rajnish Kumar, determined what neighborhood services slum dwellers would likely be willing to pay the government for, thus giving officials a reason to work with slums, rather than banishing their inhabitants to outer areas.

The researchers stress that though no one lives in a slum by choice, those who inhabit these areas make thoughtful decisions about their housing. “Once people are compelled to reside in slums as they cannot afford elsewhere,” the researchers write, “[they] still possess the capability to value or optimize on the housing attributes.”

Das and her colleagues found that slum dwellers are mainly interested in purchasing homes that have particular interior elements. Features such as an attached bath and toilet, concrete roof, brick wall, and the provision of piped water increase a house’s desirability and price, whereas the presence of an open drain in the neighborhood—indicative of the quality of the area’s environment—does not appear to matter to prospective buyers.

The distance of a home from the city’s central business district also raises real estate prices. The authors found that slum dwellers are willing to pay 30,000 rupees ($466 USD) more for a house that is closer to downtown. Average house prices in the study ranged from 369,452 rupees ($5,744 USD) in Mathura to 127,296 rupees ($1,979 USD) in Ujjain. Research conducted in 2013 by an Indian NGO and economic research firm found that 41 percent of urban slum households earn between 5,000 and 10,000 rupees a month ($78-$156 USD), while 25.6 percent of these households earn less than 5,000 rupees ($78 USD) a month.

“Sewage facilities and street lights have a strong effect on housing prices in India’s slums”

Das and her co-authors did find two neighborhood services that drive up the price of slum housing, and for which inhabitants will pay more, despite their poverty: sewage facilities and street lights. “These two services have a strong effect on house prices,” says Das. “Some cost recovery for the government is possible.”

The idea is that if the government supplies or improves these services in slum areas, residents will likely be willing to pay for them. This gives the government a financial incentive to change its policy of relocating slum inhabitants. The paper notes that the funds collected for sewage and street lights could be used “to finance other [slum] improvement programs.”

Das also advocates for the government to explicitly recognize slum inhabitants’ rights to the land surrounding their homes. “One reason people throw garbage next to their houses in the slums is because the land doesn’t matter to them,” Das says. “There, what belongs to you is inside the walls of your home. If slum dwellers are given more official rights to the land, such practices could change. People would feel ownership of the space.”