How politics pits demographic groups against each other.

Published in: www.theatlantic.com // Jon Emont // Jan 4, 2017 // Full article here

Immediately following the U.S. presidential election on November 8, anti-Donald Trump demonstrations sprang up in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles—cities that vote overwhelmingly Democratic. The protesters felt robbed: Hillary Clinton had won the majority of voters nationwide. But, like Al Gore in 2000, Clinton was hamstrung by the Electoral College, an institution designed to ensure a voice for sparsely populated states in America’s early years—and one that, of late, has spelled doom for candidates with urban-based coalitions.

The outsized influence of rural voters may seem like a unique feature—or bug—of the American political system. But a similar story recurs in places around the world. In over 20 countries, from Argentina, to Malaysia, to Japan, the structure of the electoral systems gives rural voters disproportionate power, relative to their numbers, over their more numerous urban-dwelling counterparts. And on certain issues, this can shift national priorities in favor of rural ones. In the United States in 2016, for example, the Republican platform called for eliminating federal funding for public transit, arguing that it “serves only a small portion of the population, concentrated in six big cities,” implying that Trump’s expected infrastructure bill could focus on highways rather than on urban transit networks. Global warming, of special concern to urban coastal voters, has been described essentially as intriguing speculation by the president-elect.

In America, each state, regardless of population size, receives at least three electors, and a candidate who wins a majority of a state’s popular vote wins all of its electors, assuming all those electors accept the vote (with the exceptions of Nebraska and Maine). Effectively, this means that the 259,000 registered voters of more-rural, mostly conservative Wyoming, have around three and a half times as much representation in the electoral college as the 12.5 million and 18 million voters, respectively, of large, heavily urban states like New York and California.

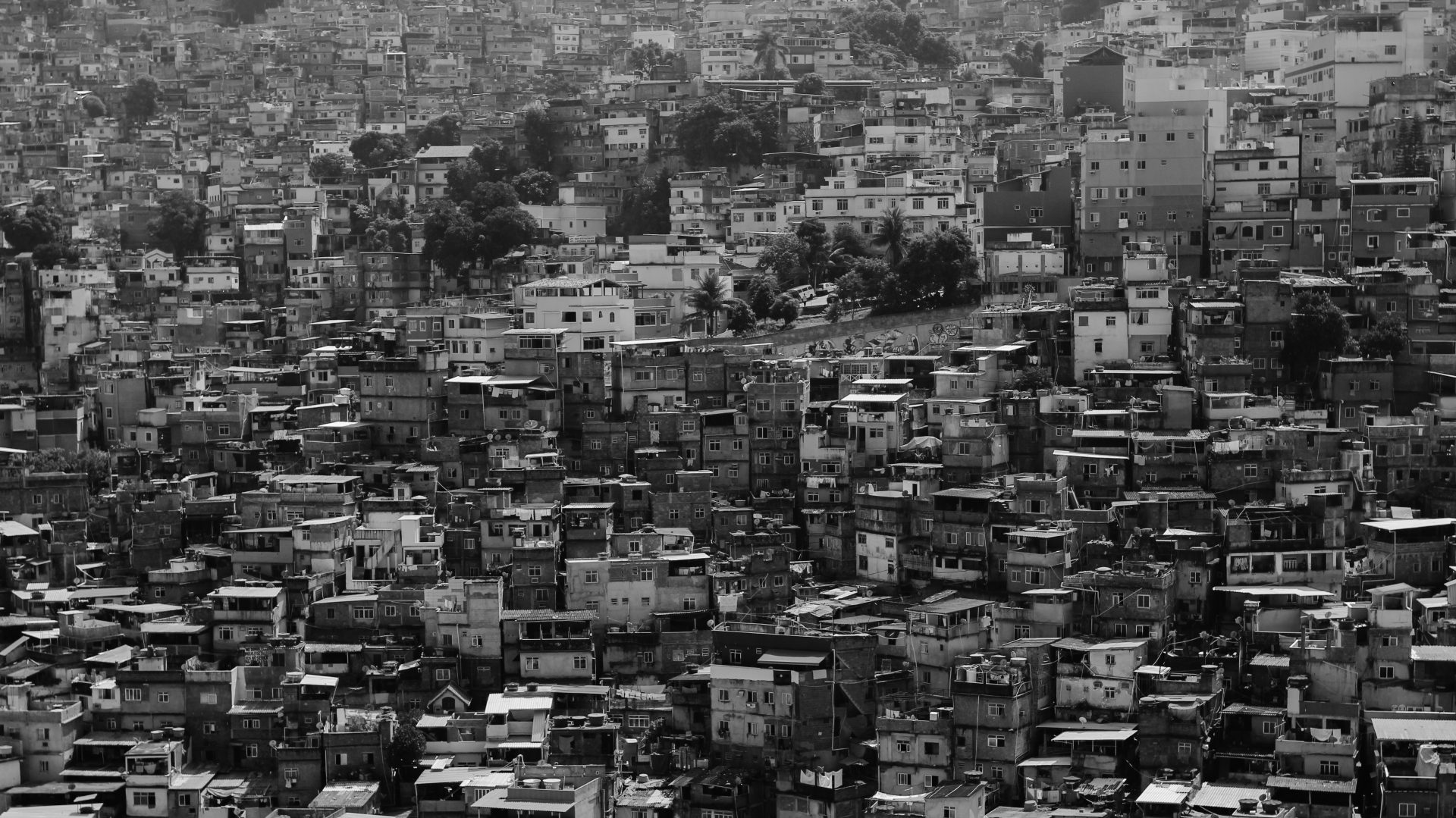

Perhaps the nightmare scenario for this kind of electoral imbalance is Argentina. The country’s upper house of parliament is modeled off the U.S. Senate—where each state is represented by two senators—so underpopulated states have the same voting power as densely populated Buenos Aires. But in Argentina’s lower house, each province, no matter its population, receives at least five representatives, thanks to reforms passed by the outgoing military government in 1983 that, in effect, gave a leg up to conservative politicians. As a result, the voters of Tierra El Fuego, a sparsely populated province, have 180 times as much representation per person as Buenos Aires voters in the Chamber of Deputies.

This has a major impact on policy. Ezequial Ocantos, an associate professor of comparative politics at the University of Oxford, said that voters in Argentina’s outlying provinces receive massive cash transfers from the federal government even as the country as a whole struggles to maintain fiscal solvency. “Some people would say [this is] at the heart of Argentina’s fiscal problems. There’s some truth to that,” Ocantos said. By many measures, outlying provinces are dramatically better-served by Argentina’s central government than is Buenos Aires, which contains around 40 percent of the country’s population. “Lots of studies show these [outlying] provinces get more infrastructure and [state] employment,” said Maria Victoria Murillo, a political science professor at Columbia. This contributes to Buenos Aires’s mounting struggles to provide affordable housing and high-quality infrastructure for its ballooning population, as well as the province’s disproportionately high unemployment rate compared with the rest of the country.

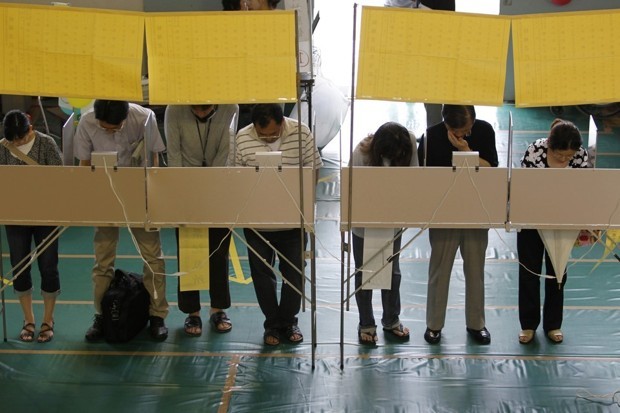

Japan’s legislature does not fare much better on this score. Its apportionment of representatives was never fully updated to reflect wide-scale migration to urban areas after World War II, when the country rebuilt its bombed-out cities and quickly industrialized. In 2013, the country’s highest court ruled that Japan’s elections existed “in a state of unconstitutionality,” due to the extra voting power wielded by rural voters. (This warning, however, failed to prompt wide-scale changes to the system.)

The result has been policies that hurt the urban majority but benefited the rural minority. Michael Thies, a professor of political science at the University of California, Los Angeles, credited the power of the rural vote in Japan with delaying structural reforms to the economy, such as lowering the country’s onerous food import tariffs and decreasing sky-high agricultural subsidies. The dominant Liberal Democratic Party has “been trying to wean the party off the organized rural vote in favor of market liberalization for nearly 20 years, but they have struggled with the ability of those rural interests to fight back,” Thies said. It’s only now, with the country’s dwindling rural voters representing such a small percentage of the population, that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has succeeded in pushing through long-delayed agricultural reforms.