Erik Berg, Chairman, Habitat Norge

Presentation from the seminar “THE RIGHT TO THE CITY – THE NEW URBAN AGENDA VS OBSERVED REALITIES IN LATIN AMERICA”, 17th of August 2017.

It is an honour and a pleasure for Habitat Norway to co-host this seminar and been given the opportunity to address you. Habitat Norway functions as a cross-sectoral information and advocacy organisation on urban and human settlement issues with focus on poverty related challenges.

The New Urban Agenda (NUA) is the outcome document agreed upon at the third “UN conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development”, in Quito, Ecuador, in October 2016. It attracted 35000 participants from 167 countries and is the biggest popular UN gathering of all times. The Agenda, contrary to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in September 2015, do not need ratification by member states. It is a lower status document which also reflects the recognition that the UN over the years has given urban development.

NUA, which has been described as long and impenetrable, is meant to operationalise the SDGs, particularly no. 11. But it gives little attention to who is going to do what with which resources. Despite its status it will for the next 20 years – up to 2036 – guide efforts around urbanisation of a wide range of actors – nation states, cities and regions, international development funders, United Nations agencies/programmes, researcher and academic institutions and civil society. Partnership between such stakeholders is a main mantra of the Agenda.

The preparatory process to Quito included a series of global conferences, regional meetings, thematic meetings and 70 “Urban thinker’s campuses” – will come back to those. From August 2015 to February 2016 a group of 200 experts known as “policy units”, there were 9 of them also with representation of NIBR – came up with important recommendations – also with regard to future research – for the drafting and implementation of NUA. Also relevant was the work of the General Assembly of Partners (GAP), funded by the Ford Foundation, and its 16 stakeholder groups where NGOs and academics were very well represented. GAP was meant to expand constituencies also to include rural based organisations. It is the intention of the UN that many of these activities, partnerships and measures will continue in the follow up of the Agenda. There is vide scope for everybody – individuals, institutions and organisations – to join this multilateral arena.

The main challenge for the third Habitat Conference was how the development potential in an urbanized world could benefit the poorer stratas of population as part of broad urban development. “Leave no one behind” was underscored”. The question is if it leaves everyone behind. NUA seeks to create a mutually reinforcing relationship between urbanisation and development. The idea is that the two concerns will become parallel vehicles for sustainable development. The Agenda seeks to offer guidelines on a range of “enablers” that can cement this relationship. This includes,on the one hand, “development enablers” that seek to harness the many, often chaotic forces of urbanisation, in ways that on the macro level generate across the board growth, promote national urban policy and laws, institutions and systems of governance.

The Agenda’s “operational enablers”, on the other hand, are meant to promote urban sustainable development more on micro and meso level. When implemented they would result in better outcomes for patterns of land use, how a city is formed and how resources are managed. NUA underscores three operational enablers, referred to as the “three legged approach”: local fiscal systems, urban planning and basic services and infrastructure.

Notable in NUA was the new focus on urban rights, especially the so-called “right to the city”, which has never before been agreed upon as language in a UN member-state adopted document. Habitat II in 1996 referred to “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms”, whereas Habitat I in 1976 only underscored that “adequate shelter and services are a basic human right”. The “right to the city” was the most contentious point in the negotiations and nearly derailed them many times. A coalition called the “Global Platform for the Right to the city” – with Habitat International Coalition (HIC) as the main driver – led efforts to insert language affirming these rights with particular support from the Brazilian and Ecuadorian governments.

The language of the “rights para”, number 11, ultimately read “We share a vision of cities for all while noting the efforts of some national and local governments to enshrine this vision, referred to as right to the city, in their legislations, political declarations and charters”. Para 13 outlines what “a vision of cities for all” looks like. It hits such issues as the social function of land, right to adequate housing, gender equity and informal economies. What was lost in the negotiation process was for instance language on “the city as a common good”. The European union favoured language describing cities as “competitive”. Which tells a lot.

What also is lacking is mentioning of “the human rights based approach”, the methodology whereby people claim their entitlements defined in constitutional rights through self organisation, empower-ment and strengthened voice vis a vis duty bearers – that is local, national and international institutions.

One initiative that will continue from Habitat III preparations into implementation, is the “Urban Thinkers’ Campuses”, initiated by the World Urban Campaign. This is an advocacy and partnership platform to raise awareness about positive urban change. It is coordinated by UN Habitat and driven by currently 180 partners and networks from around the world. The “Campuses” are day long or multi day events organized by universities, activists, think tanks, research institutes, NGOs and grass-root organisations where dialogue with local government on local challenges is central. Their inputs to NUA were included in a final report called “The City we need 2.0”;

The World Urban Campaign will launch a new global campaign for the next years on measuring, designing, financing and managing “The City we need 2.0”. Habitat Norway will consider to arrange an “Urban Thinkers Campus” next year. Maybe in cooperation with NIBR? In Brazil in 2018 – INCITI – which is a university and college in Recife, Brazil, will host three campuses throughout Pernambuco, a state in the North East, taking the concept to more secondary cities and rural areas in addition to the capital Recife reflecting a “territorial” urban approach.

Habitat International Coalition also plans to harness the wealth of research and analysis prepared during the Habitat III process, funnelling it into what is called “The Human Rights Habitat Observatory”. The project would focus on monitoring the follow up of the new global agreements against the human rights obligations to which nations are bound under international law. Not just the NUA but also the SDGs, the Paris climate agreement and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction will be under scrutiny.

The follow up of NUA has, however, come to a standstill. Partly because UN Habitat again is on the brink of financial collapse – as it was after Habitat II in 1996. But partly also because NUA has requested the UN Secretary general to submit through an Evaluation Panel to the General Assembly during the coming session this autumn, an evidence- based and independent assessment of UN Habitat’s work with the view to enhancing its effectiveness, efficiency, accountability and oversight.

The Panel published its report a fortnight ago. It draws attention to and criticises the failure within the UN system to acknowledge the pace, the scale and the implications of urbanisation. It underscores the dependence of the 2030 Agenda on the direction of urban development. And it formally opens up in the state led UN for non state-players such as civil society, local government and private business through own, separate committees. To support UN Habitat’s efforts the Panel proposes the establishment of UN Urban, an independent coordinating mechanism to convene all UN agencies and partners on urban sustainability modelled after UN Water and UN Energy. It recommends for UN Habitat a renewed commitment to the normative mission with innovative approaches to financing this role.

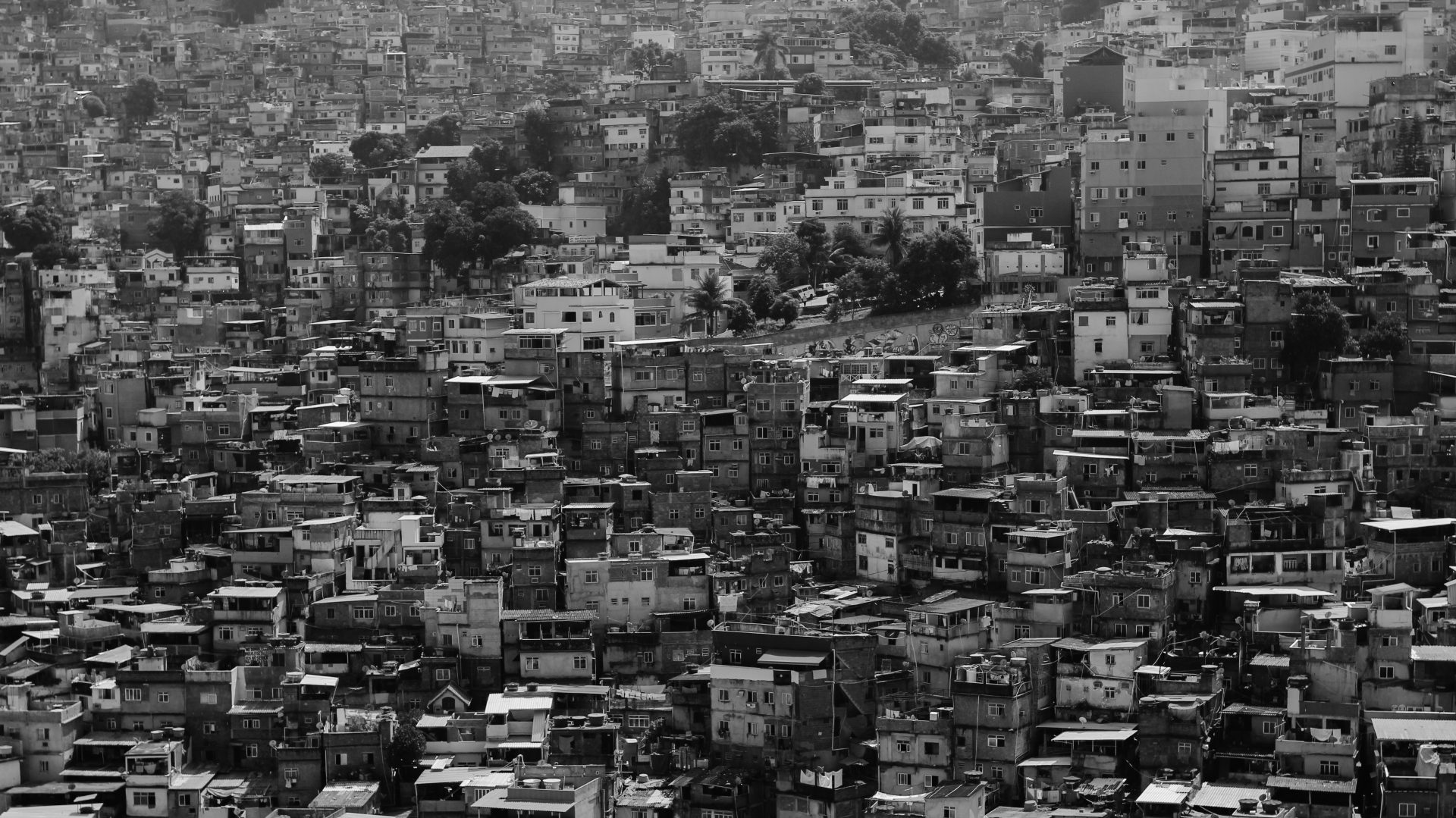

Our present day context is the neoliberal world, dominated by what has been termed “an all you can eat mentality – privatizing gains and socializing losses”. This is fatal because what we see evolving as a result and as pointed out by your Norwegian- Brazilian collaborative project are mega projects with huge footprints that erase much of the public tissue of people, streets and squares. These forces privatize and de-urbanize city space – no matter the added density.

At the same time, it is in the public space – the street, the square, the park – that the right to the city is most often demanded. It is in the cities to a large extent that the powerless have left their imprint – culturally, economically and socially – and forged alliances and advocated policies with great success.

The protests in Istanbul’s Taksim square against the development of Gezi Park, the occupation of Zucotti Park in New York, the popular manifesttaions in the streets of Hong Kong and the “Nuit Debout” protests in Paris’s “Place de la Republique and in Rio de Janeiro in 2013 before the Olympic Games- all show that public space is the threatened sphere where citizens can demand change.

As your collaborative project shows, both NGOs, INGOs and academics have important roles to play in this struggle. There is a particular need internationally after UN Habitat’s Action Committee on Forced Evictions but also the Centre for Human and Rights and Evictions in 2011 was closed down, to globally document and share people based initiatives and experiences of struggles against evictions, forced or market driven, including how groups are securing rights to adequate housing, to legal security of tenure and freedom from arbitrary destruction and dispossession. World Urban Campaign, General Assembly of Partners and Habitat International coalition represent future foras very relevant for this purpose for stakeholders both in the Global North as well as the South.

My second main concern after forced evictions is rural to urban migration, particularly in Africa and Asia, where 90% of projected increase will incur. And where resources are most constrained and development challenges most intense. Very few take responsibility for the new groups of migrants, refugees and evictees settling close to but outside city borders. They are not part of the formal administration of municipalities. The apparatus that provides social services are lacking. This gives no political influence for poor people.

It is necessary to accept an expanded definition of the city. This will have major implications for planning, norms, land tenure regimes and access to basic amenities. Critical to the goal of inclusion is data. Urban dwellers living in informality are frequently undocumented in formal data systems. Even when data is collected, there is the issue of disaggregation. Data are most often presented in terms of rural and urban averages. This fails to reflect the complexity of the urban landscape and the large disparities within urban areas. Efforts to document the full range of urban realities, whether by strenghtening formal systems, or supporting existing informal strategies, such as the “enumerations” by urban poor federations, are essential. So are capacity building contributions of NGOs and researchers.

Today the lead activist role is played not so much by urban NGOs but more by urban grassroot movements. The role that women and girls are playing in these movements is remarkable. They contribute decisively to organize groups such as street vendors, garbage pickers, home workers, slum and street dwellers, the homeless, locally, nationally and globally. Urban NGOs play important support functions with regard to service delivery and teaching people their rights. They represent continuity in a world of shifting political and bureaucratic alliances although there are trends that big NGOs through provision of funding are co-opting social movements, neutralising their effects through bureaucracy, policies and constricting guidelines.

Partnership is essential for synergy. Let me mention a model organisation in this respect. In Women’s Informal Employment: Organizing and Globalizing (WIEGO) three broad constituencies come together: researchers and statisticians who carry out research, data collection and analysis on the informal economy;-membership –based organisations of informal workers such as trade unions, cooperatives and worker associations; practitioners from development agencies (inter-governmental and non governmental) who provide services to or shape policies towards the informal workforce. It advocates international trade unions and tries to put informal sectors workers on the agenda of governments and international organizations. It has observer status with the International Labour Organisation from which it also receives financial support.

Latin American policies and practices of decentralization and local governance are more developed than anywhere else in the world. So are many of your city constitutions which legitimize popular action based on rights.The learning potential of innovations in “participatory budgeting”, the Rapid bus transport system” or “green urban acupuncture” approaches (both of Curitiba) are being now globally recognized and copied. The United Cities and Local Government (UCLG), organizing one thousand local governments on all continents, are co-ordinating twinning or mentoring arrangements between cities in Brazil and Southern Africa, particularly Mozambik and Angola, building competency and capacity, piloting programme and project approaches. Researchers and NGOs on both sides should be more actively part of such partnerships. We need to learn from your accumulated experiences and wisdoms.

Erik Berg