The Shift: A Global Movement to Reclaim the Right to Housing

Delivered By: Leilani Farha // UN Special Rapporteur on the right to housing // 4th of October 2018

I am Leilani Farha, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to housing – I was appointed in 2014 and have been immersed for the last four years in understanding global housing conditions and working on global solutions.

As I travel the world, and meet with governments, Mayors, individuals and families, NGOs, national human rights institutions and many others, I am left with little doubt that access to adequate affordable housing in cities is the most pressing issue of the day and is certainly the most pressing issue in most people’s lives.

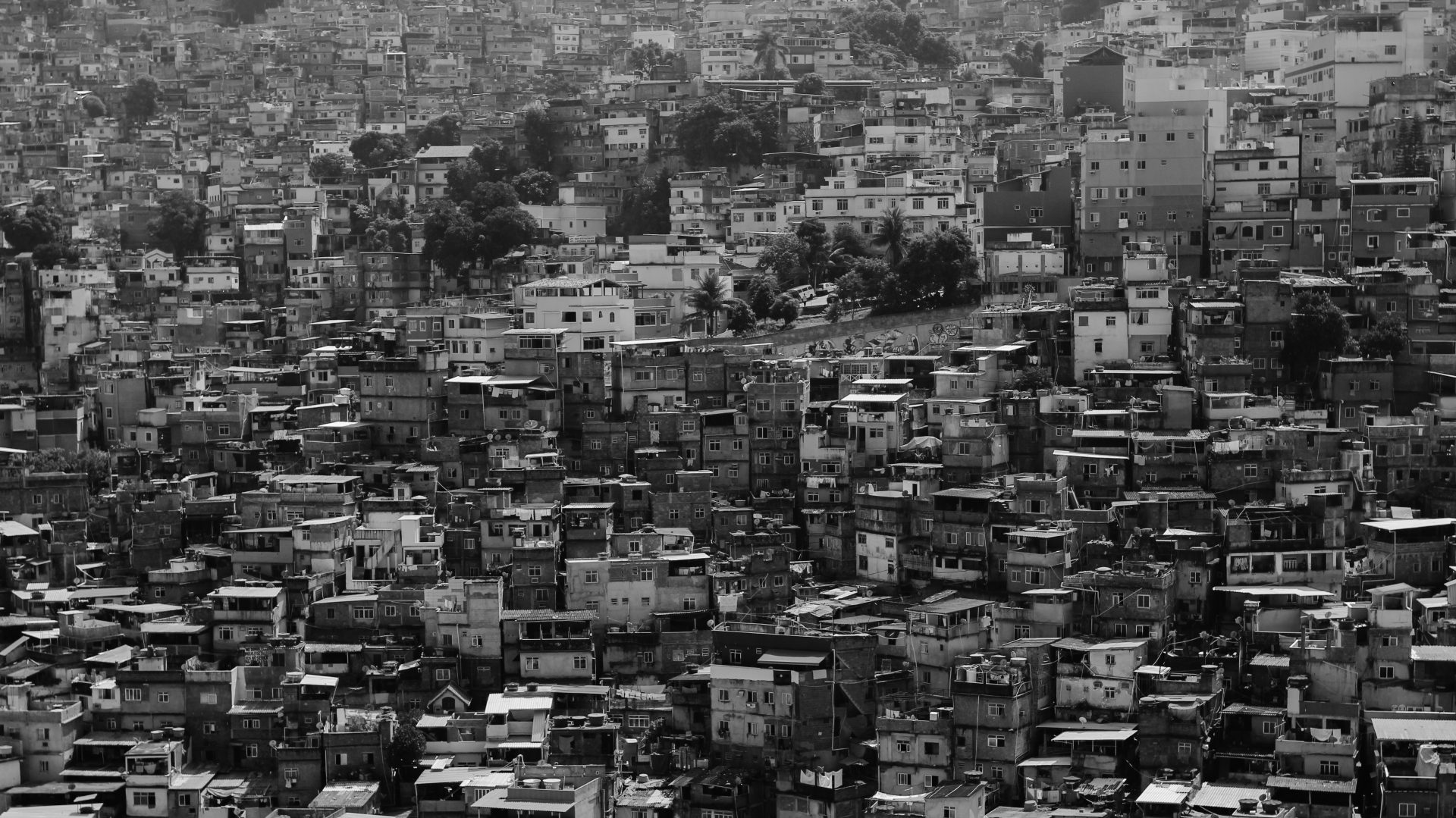

Half of humanity – 3.5 billion people – live in cities. By 2030, this will increase to almost 60 per cent of the world’s population.

For far too many people worldwide, housing conditions are simply deplorable, lacking many of the characteristics required for housing to be considered adequate under international human rights law.

It is estimated that 1.6 billion people are inadequately housed worldwide and that close to 900 million people – or a ¼ of the world’s population – live in informal settlements and encampments in both the global North and South often lacking even the most basic of services like water and electricity. That’s ¼ of the world’s population.

There are few cities that I visit – in the North or the South – where I don’t see people having to live on the streets, forced to eat, sleep, cook and defecate on sidewalks. In San Francisco I met a young guy living under a bridge, we talked while he cooked a quesadilla on a little stove he had rigged up, with human feces on the pavement before us. In Delhi, I sat on the pavements with families who for two generations had known no other life.

That these kind of housing issues are now common in the North is frankly shocking and shameful. How is it now acceptable that hundreds of thousands of people in Canada, the US, western and eastern Europe, Australia and New Zealnd are living on the streets? Northern countries were supposed to have reached a level of development that would ensure the security and dignity of their people. Western nations are supposed to leverage their wealth to assist less affluent countries to address housing inadequacy.

And yet, I am increasingly seeing and hearing of individuals, families and even entire communities being evicted from their homes to make way for luxury flats and short-term rentals, or because their rent has increased but their income hasn’t.

It is now common for private equity or global asset management firms to use their unimaginable stores of wealth to purchase entire neighbourhoods, only to use housing as a vehicle to grow profits for a few who have no intention of living there, while displacing the many who do.

Investors, including pension funds and individuals of ultra high net worth, are encouraged by governments and the financial sector to park their excess capital in residential real estate as a safe place to hide and grow money. I have seen this in Barcelona, Dublin, New York, Uppsala …

While these sorts of practices are more common in the North – I also saw just now in Egypt that this model is being exported to the Global South as well. And it is so attractive to Southern countries because the prospect of investor money is too tempting to pass up, in light of lean budgets and ambitious commitments made under the Sustainable Development Goals that are unlikely to be achieved without substantial private sector investment.

In this regard, as governments move forward to meet their commitments under Goal 11 of the SDGs – which includes a commitment that they upgrade slums – I am concerned that we will see a spike in forced evictions contrary to international human rights law. In a number of countries I have already seen that slum upgrading is resulting in poor housing conditions that while potentially marginally better in the short term, do not meet human rights requirements and may very well simply become new slums in the longer term. Made worse by the fact that many of these schemes involve public-private partnerships with little human rights accountability imposed on the private actors being brought in to produce the housing.

If we do not find housing solutions, cities will not be able to meet their human rights obligations or their commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals. Without access to adequate, secure and affordable housing there is no equality, no health and well-being, no access to education or employment and there is no end to poverty.

So what’s the solution to all this? I am pretty sure that tinkering with existing programs won’t work. And developing new policies and programs based on existing frameworks won’t either – why would they? Those frameworks are not clearly not producing positive results.

I think a fundamental shift is required – a shift whereby housing is recognized and implemented as a human right, not a mere matter of policy, nor a commodity, and certainly not something to be left to the whims of unregulated markets and private developers.

Inadequate housing, homelessness, and forced evictions are all an assault on security, dignity and life and as such go to the heart of what triggers human rights concern. Human rights violations of this nature demand human rights responses.

What’s the value of such an approach?

A rights-based approach to housing clarifies who is accountable to whom: all levels of government are accountable to people, particularly marginalized and vulnerable groups, who are recognized as rights holders, not merely the beneficiaries of charity.

And human rights incorporates universal norms providing a common purpose and shared set of values to laws and policies.

I recently presented a report to the Human Rights Council which articulates for States and cities 10 core principles that should inform a human rights based strategy including:

Prioritizing those most in need including committing to eliminating homelessness.

Strategies must put in place institutional mechanisms to monitor progress and hold governments accountable to goals and timelines.

Strategies must be based in law and affirm the right to housing as a legal right, and they must clarify the obligations of private actors. If States and cities intend to rely on the private sector for housing it must be understood that the obligation to realize the right to housing cannot be delegated, it remains with them. Cities must adopt robust measures to regulate and reorient financial, housing and real estate markets to ensure inclusive cities and affordable housing.

Strategies must inclue provisions for the upgrading of informal settlements, but in doing so, they must shift away from top-down approaches to the upgrading of informal settlements to one that embraces the knowledge and expertise of communities to improve their living conditions. Informal settlements must be understood as not just violative of human rights but equally a profound expression of individuals, families and communities claiming their place and their right to housing. They are “habitats made by people”, who are creating homes, culture and community life in the most adverse circumstances. Strategies would have to include Core principles like the right to participation and inclusion and monitoring and access to justice mechanisms.

While it’s essential for individual cities and States to develop and implement human rights based strategies, the only way that we can achieve the kind of Shift I am talking about – a fundamental paradigmatic shift on a global scale – is by developing a global movement of diverse stakeholders who are willing to challenge the status quo. Perhaps not surprisingly Cities – which are uniquely situated, on the front lines of the housing crisis – are currently leading the way in this regard.

In a short time, we have seen the cities of Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin, Mexico City, Montreal, Montevideo, New York, Paris, and Seoul, pledge to articulate very clearly that housing is not gold, or oil, it is not a commodity, it is a fundamental human right, that can be the difference between a productive and healthy life or no life at all.