Pricey downtown real estate and safety concerns are among the factors.

Published in: www.citylab.com // By: Irene Caselli // Feb 5, 2016 // Full article here

Having to show an ID, name the passengers in your car, or reveal the contents of your trunk when you come home is not something that would appeal to everyone. But in and around Argentina’s capital city, Buenos Aires, gated communities with guards have become synonymous with safety and exclusivity.

Barrios cerrados, or “closed neighborhoods,” as they are known, now cover about 150 square miles of the region—twice the territory of downtown Buenos Aires. Their rapid, largely unregulated growth is putting a strain on environmental resources and public services, not to mention changing the social fabric of the city.

Situated along the shores of River Plate, Buenos Aires lies on one end of the vast Pampas plains. Land in these suburban communities is much cheaper than in the city, so many first-time homebuyers choose these gated communities.

“I was always resistant to the idea of living in a barrio cerrado,” says Gustavo Grahmann. “I grew up in a regular neighborhood and I associated gated communities with living in a bubble, away from reality.”

Grahmann, a 34-year-old wholesale retailer, and his wife decided to buy their first house in a gated community in the northern area of Pilar after their daughter, who is now one, was born.

“We could buy more for less money, compared to areas that we liked more,” says Grahmann. “It was a no-brainer.”

Depending on the amenities available and the distance from the city, housing in a gated community can cost about half as much per square foot (around $110) as in downtown Buenos Aires, says Haydeé Burgueño, a real-estate agent in the area.

Safety is also something buyers have in mind, especially when they have children. Buenos Aires has a relatively low homicide rate, but crimes like home break-ins, car thefts, and muggings occur often.

“It is not common anymore to take kids to the park because it’s perceived as unsafe,” says Burgueño. “Parents are willing to make an effort to work downtown and commute, so that their children can run around freely outdoors.”

Argentina’s love affair with gated communities began in 1930. That year, the Tortugas Country Club opened, an exclusive destination 25 miles north of the city center that had polo fields and a white, colonial-style clubhouse surrounded by bougainvillea.

Initially, this and other country clubs (which are known in Argentina simply as “countries”) were meant for weekend or holiday stays, since they were far from the city and had huge fields devoted to sports like polo, tennis, and golf.

Things started changing in the 1990s, under the leadership of then-President Carlos Menem, who pushed for free-market reforms.

“The availability of cheap land, the development of motorways, neoliberalism, and the heightened feeling of insecurity encouraged a new dream: living in the lush and safe suburbs, without being too distant from downtown,” says Guillermo Tella, an urbanist, academic, and executive director of strategic planning for the City of Buenos Aires. Convenient long-term mortgage plans became available in the 1990s, too, supporting the construction boom.

Even after Argentina’s economy collapsed in 2001, gated communities remained popular due to rising insecurity, prompted by crimes like express kidnappings (when a person is held up at gunpoint and forced to withdraw money from an ATM, then released). Mortgage loans were harder to come by, so gated condos with swimming pools and barbecue areas were developed to meet lower budgets.

As a result, the greater Buenos Aires area expanded, pushing the suburban frontier farther and farther. Now barrios cerrados come in all shapes and forms: one emulates a Caribbean resort, another looks like a medieval Italian town, while some, such as Nordelta, have grown into proper cities.

New malls, with cinemas, restaurants, and cafes, have popped up around the newer gated communities, and companies moved their headquarters to these areas, especially to the north of Buenos Aires.

But the growth happened so fast that it was too much for the preexisting infrastructure.

“Pilar used to be a small and lovely provincial town,” says Burgueño, who was born in the area. When the population soared, it put a strain on the health and school systems; public transit still leaves much to be desired, and the road network can’t handle all the cars.

Grahmann drives more than 25 miles each way to get to and from work. He has to leave by 7 a.m. to avoid rush hour or it takes him twice the time. There are no direct buses or trains that go downtown.

Suburban development has also put a strain on natural resources. It “generated a huge transformation of rural land and ecosystems, such as wetlands and floodplains, into private neighborhoods,” Tella notes.

Many of these private neighborhoods, some with artificial lakes or canals, have affected ecosystems that are vital to water drainage and crucial to containing floods. Studies have shown that these changes have aggravated flooding in certain areas, such as the basin of the Luján River, north of Pilar.

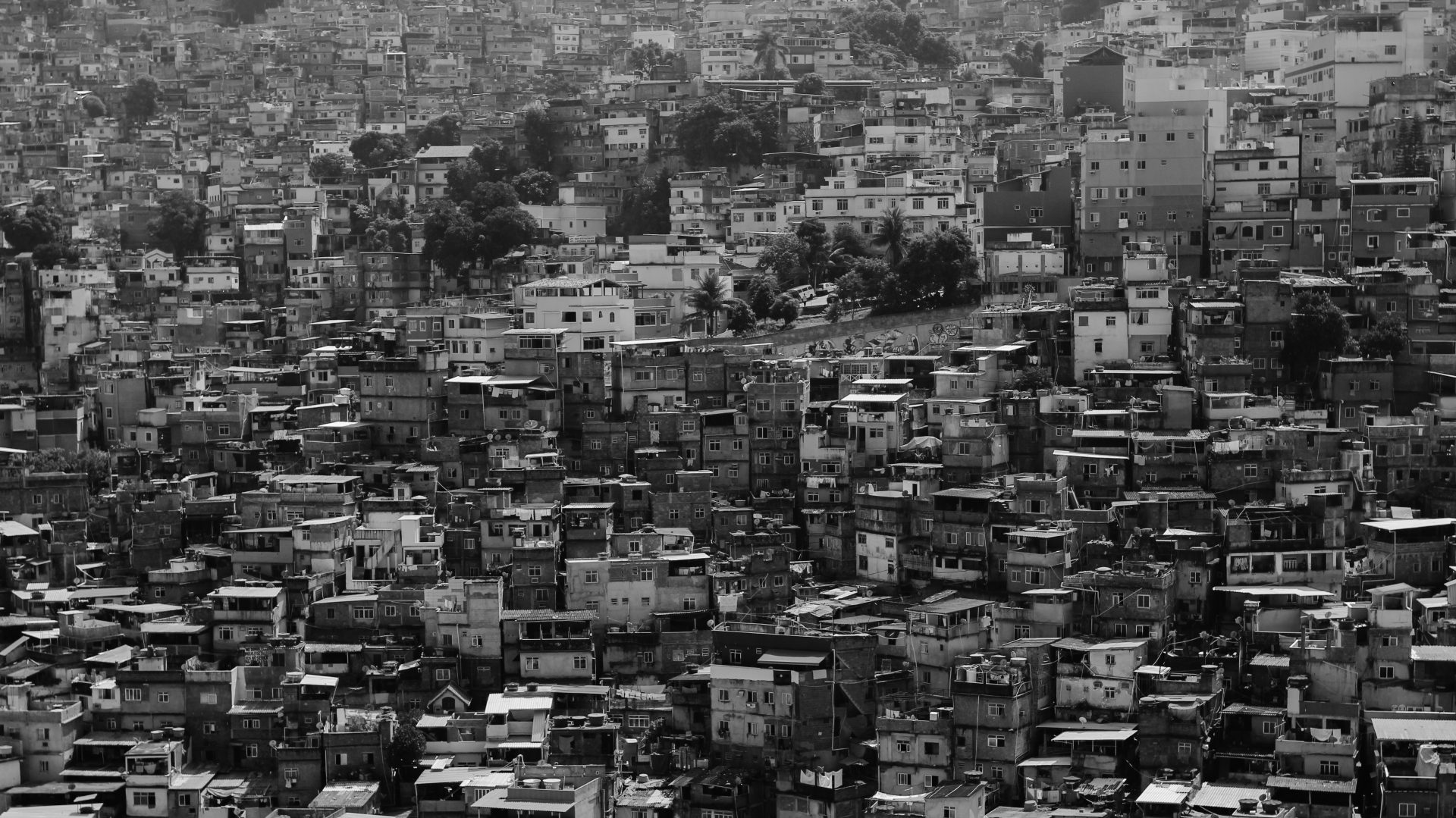

While the new communities have created work clusters away from the congested downtown, they have not fostered social integration. Often the walls of the enclaves are surrounded by precarious shacks that house those who work as gardeners or maids on the other side.

A law passed in 2012 in Buenos Aires Province gives the provincial government the right to tax new gated communities a tenth of their land value in order to invest in social housing, but this has not been implemented so far.

In his barrio cerrado, Grahmann says residents are trying to mix with people who live in the surrounding areas, organizing parties at Christmas and hiring only locals as guards.

“We need each other. We need the people that live in these areas to help us out in our homes. And we create good work opportunities,” he says. “More integration is necessary.”